Prisoner found Islam — and then freedom – MercuryNews.com

Prisoner found Islam — and then freedom – MercuryNews.com

Andre Wiley’s freewheeling youth abruptly ended the night in 1989 he fired a hail of bullets at a hamburger stand, killing a man and wounding several others because their clothing marked them as rival gangsters.

Wiley is a different man 23 years later. He’s Yusuf Wiley, 42, deeply committed to a new religion and on a mission to help California’s most troubled men, Muslim or not, purify their hearts.

Thousands of California prisoners, mostly African-Americans, have converted to Islam behind bars, but they struggle to find their place when they get out.

Wiley is an exception. Many who know him hope he also represents a change that could improve a vast state prison system with a poor record of rehabilitation. Sixty-five percent of California’s felons return to prison within three years.

For more than a decade, Wiley was a key figure spreading a deeply contemplative approach to Islam across many of the state’s 33 prisons. Religious devotion informed his activism, but Wiley said he had a broader motivation: getting therapy, counseling and fellowship to prisoners offered little from the state.

“The inmates have been the ones running the programs and giving the therapy,” Wiley said. “We don’t mind doing it. We’re trying to help each other.”

Two weeks after his release, the man who taught himself verses from the Quran in his prison cell is getting requests to teach classes at Bay Area mosques.

If Wiley were to become an imam leading worship at a mosque, “I would put him in the top 10 percentile” in the United States, said Shaykh Rami Nsour. He directs the Tayba Foundation, a religious education group that encouraged Wiley to move to the Bay Area upon his release.

“The education he’s got is very extensive,” Nsour said. “He’s not just a student. He could easily take on the duties of being an imam, leading a congregation.”

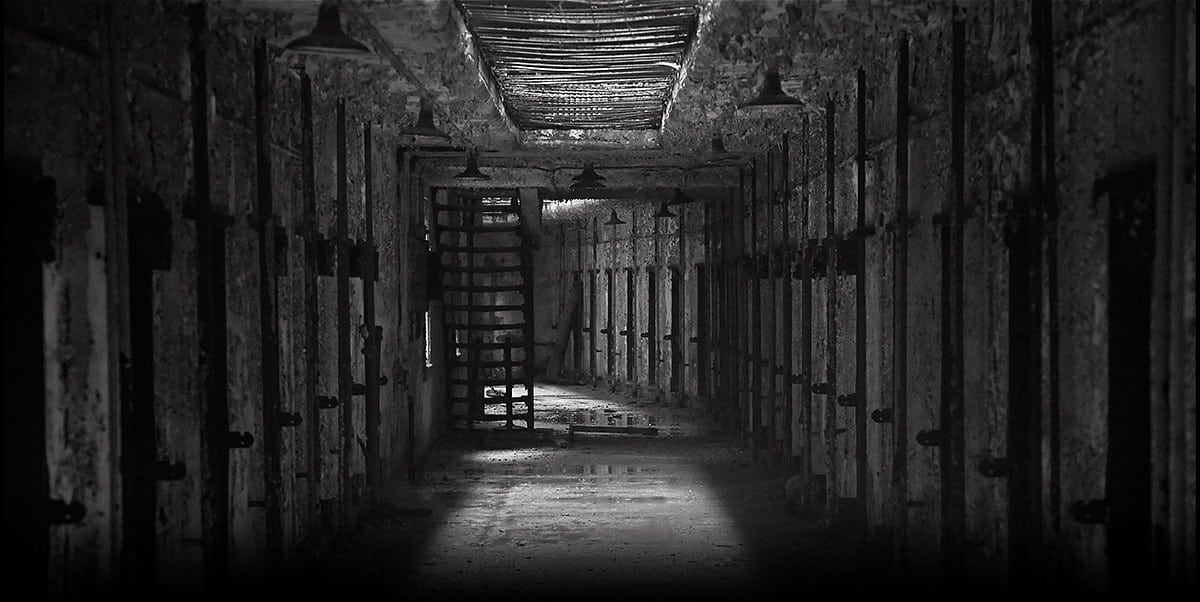

Wiley’s transformation began after a 1993 prison fight earned him nine months in “The Hole,” a windowless, high-security cell. Hopeless, alone but bound by gang allegiances, he found an almanac passage introducing Islam.

“I embraced it on the spot,” he said.

Drawn at first by the religious discipline and the discovery that his pre-slavery African forebears were probably Muslims, Wiley dug deeper into Islamic scriptures.

He found there the science of “ihsan” — a word Muslims translate as virtue, intention or doing “beautiful things” — and instruction in the careful self-examination by which the faithful can purify themselves of psychological ills.

“It’s about recognizing your heart is diseased with envy, arrogance, hatred,” Wiley said recently. “And it shows you how to rid yourself of those diseases.”

Such redemption for Muslims, Nsour said, requires a deeper commitment than the basic requirements of praying five times a day, fasting on certain holidays and a host of other traditions.

“Going inward — that’s when the change begins,” Nsour said. And that’s what Wiley did and is teaching.

Free after two decades behind bars, Wiley cheerfully engages with everyone he passes. Strangers gravitate to him, asking for money — which he gives — or to borrow his cellphone, which he offers. Many find him a model for those looking for a way out of criminality and incarceration.

“Clearly, you’ve gone through phases in your life, and there was a time when remorse was the farthest thing from your head,” California Parole Commissioner Howard Moseley told Wiley at his final parole board hearing in December, according to a transcript.

“It’s apparent that you began to make a transformation once you adopted your faith.”

Wiley joyously walked out of the Central Valley’s Avenal State Prison on May 24, escorted by prison officers who took him 200 miles north to the East Bay.

“There’s no words for it. There’s really no words for it,” he said as he walked across the Hayward grounds of the Tayba Foundation in his first hour of freedom, embracing old friends who had awaited his arrival. Many were Muslim men and fellow converts who left prison before him and found success in jobs and marriages.

Wiley caught the first glimpses of an era of American life he had missed.

“This is a laptop, huh?” he asked a friend at the Tayba office, where he now works and plans to expand his advocacy and to guide the inmates he left behind.

It was Wiley, said former inmate Malik Williams, who enabled him to begin the self-reform that finally freed him from prison.

“He’s very humble, very pious. Hundreds of people have come to his presence,” Williams said.

Williams heard about Wiley’s release and came to visit him at a Friday prayer session in Oakland. Another former inmate drove his family up from Los Angeles for the occasion.

The change pleases Sampson and Betty Wiley, his parents whose hearts were broken so many years ago by their son’s crime. Married for 59 years and members of the same neighborhood church since the 1950s, the couple took a while to adjust to his conversion to Islam. They still call him Andre, not Yusuf.

“As a member of the Church of Christ, I didn’t like it, per se, but if that’s his way of expressing himself, if that’s going to make him a stronger citizen for our country, if that puts him in proper perspective, I can tolerate it,” Sampson Wiley said. “I will love him just as much.”

Yusuf Wiley said his parents did their best to raise him, but unlike his older siblings, he got caught up in the gang violence that permeated his South Central Los Angeles neighborhood in the 1980s.

“He started living two lives,” Sampson Wiley said. “He’d go to church with me every Sunday. But when he’d leave church, he’d get into his own thing.”

Wiley pleaded guilty to second-degree murder for the drive-by killing, and a judge sentenced him to 16 years to life.

He became eligible for parole in 2001, but his requests were denied every two years. The parole board said OK on his fifth try.

Avenal State Prison workers lauded him for founding a secular self-help network, the Timeless Group, which still meets weekly, and for being an influential peacemaker.

“Repentance is the leader of all change,” Wiley said. “I knew I had to repent, seek forgiveness. Every person I came into contact with who was a Crip, or a rival, I would apologize, tell them this is not my lifestyle anymore.”

Wiley has apologized to his victim’s family and says he blames no one but himself for his crime.

He wanted to move to the Bay Area instead of returning to Southern California because of the thriving Muslim community he has been a part of since the 1990s and to avoid the gangsters who still rove outside his parents’ home.

As he began to study the faith, he listened to the recorded lectures of Shaykh Hamza Yusuf, an American-born Muslim convert who in 1996 co-founded the Zaytuna Institute, a Hayward think tank for Muslim scholars that is now a religious college in Berkeley.

Wiley wrote to the influential shaykh but got no response. Years later, after more study of Islamic jurisprudence, he wrote asking how the rules of fiqh, a moral and ritual code of conduct, apply to prison life.

“That got his attention,” Wiley said. “That’s when they started sending me little booklets.

Ten years ago, Nsour began instructing Wiley in Islam by letter and long-distance phone calls.

“I saw he was very, very motivated,” Nsour said. “Whatever texts I sent to him, he would soak them up, ask specific questions. We had phone lectures. He’d call me collect. For a couple years, it was three times a week.”

Wiley in turn taught fellow inmates. Nsour is confident Wiley could become a mosque leader if he wants to but also knows “there’s a greater community he wants to serve.”

California’s tens of thousands of prisoners and the legions of youths on a dangerous path to join them could find a better way with more guidance, more introspection, Wiley said.

“People don’t believe they have it in them to change until they see somebody like me who went through what I went through, coming from a gang background,” he said.

“They see hope — and that gives them a little of what they need to change.”

—

Shaykh Rami Nsour works with providing prison inmates with Islamic learning at Tayba Foundation and is also a teacher at SeekersGuidance

Courses Taught

- GEN160 – The Rights of Parents

- GEN175 – Prohibitions of the Tongue