Is It Permissible to Print the Quran with Colored Letters?

Answered by Shaykh Anas al-Musa

Question

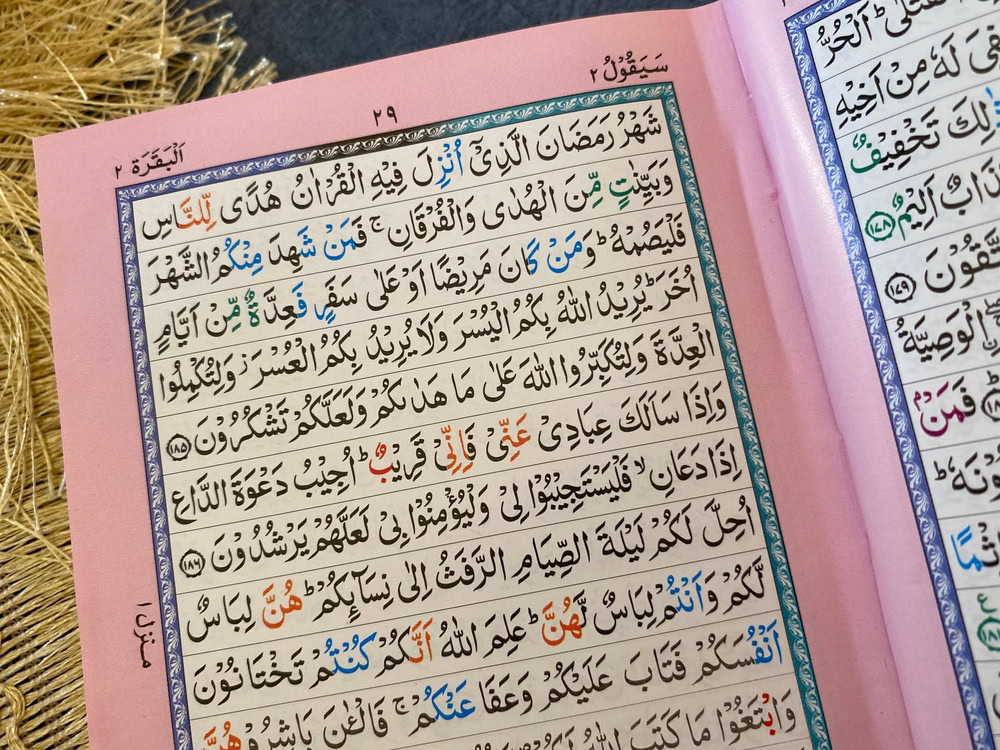

Is it permissible to print the Quran with colored letters indicating Tajwid rules?

Answer

In the Name of Allah, the Merciful and Compassionate.

All praise is due to Allah, Lord of all worlds, and peace and blessings be upon the Messenger sent as a mercy to the worlds, our Master and Prophet, Muhammad, and his Family and Companions.

Printing the Quran with Colored Letters for Tajwid

Yes, it is permissible to print the Quran with colored letters to indicate the rules and principles of tajwid, such as coloring the rules of the silent nun in one color, the rules of the silent mim in another color, and the rules of elongation in a different color, and so on.

This is a legitimate practice for a legitimate purpose, as long as these colors do not show any disrespect to the Quran, and the intention is to facilitate and simplify the correct recitation and to perfect the recitation. It is also important that this practice avoids confusion and does not add anything extraneous to the Book of Allah. The Quran should always remain a sacred book containing the words of Allah, and not be turned into an ordinary book or a school textbook.

Historical Context and Practices

The righteous predecessors (Salaf) used to do something similar when they marked the vowel signs of Quranic words in different colors to distinguish the script from the diacritical marks, thereby preventing errors in recitation. The details are as follows:

The righteous predecessors undertook the task of marking and diacriticalizing the letters of the Quran. The Uthmanic codex initially did not have diacritical marks. The diacriticalization of the Quran is famously known to have occurred during the reign of Abdul Malik Ibn Marwan.

He observed that the expanse of Islam had widened, and the Arabs had intermixed with non-Arabs, which threatened the purity of the Arabic language. The ambiguity and confusion in reading the Quran became prevalent among the people, making it difficult for the masses to distinguish between the letters and words of the Quran without diacritical marks. Therefore, he ordered Hajjaj to address this significant issue.

Hajjaj appointed two prominent figures who combined knowledge, piety, and expertise in the fundamentals of the language and the various modes of Quranic recitation to tackle this problem: Nasr Ibn Asim al-Laythi and Yahya Ibn Ya‘mar al-‘Adawani. They succeeded in their task and diacriticalized the Quran for the first time, placing diacritical marks on all similar letters, ensuring that no letter had more than three diacritical marks. This practice spread among the people and had a profound effect in eliminating the ambiguity and confusion in the Quranic script.

Marking and Diacriticalizing the Quran

Historians agree that the Arabs in their early days did not know how to mark the letters of words with diacritical marks due to the purity of their language and the fluency of their tongues. However, when new nations, including non-Arabs who did not know Arabic, entered Islam, and the purity of the Quranic language was threatened, the practice of marking words with diacritical marks began. It is said that Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali heard a reader recite the verse:

“Allah and His Messenger are free of the polytheists.” [Quran, 9:3], but the reader mistakenly recited it with a genitive case for the letter in “His Messenger (ورسولُه),” changing the meaning to indicate that Allah disavowed His Messenger.

This grave mistake alarmed Abu al-Aswad, who then said: “Allah’s glory is above disavowing His Messenger.” He immediately went to Ziyad, the governor of Basra, who had previously asked him to create signs to help people read the Quran correctly. Although Ziyad had delayed his response, this incident prompted Abu al-Aswad to act, saying:

“I have agreed to your request, and I think we should begin by adding diacritical marks to the Quran. Send me thirty men.”

Ziyad gathered them, and Abu al-Aswad selected ten from among them, eventually choosing one man from the tribe of ‘Abd al-Qays. He instructed him:

“Take the Quran and a different colored ink. When I open my lips, place a dot above the letter (indicating the fatha). If I round my lips, place a dot beside the letter (indicating the damma). If I lower my lips, place a dot below the letter (indicating the kasra). If any of these movements are followed by nasalization, place two dots (indicating the shadda).” He began with the Quran and continued until he had marked the entire text. [Ibn Anbari, Idah al-Waqf wa al-Ibtida; Dani, al-Muhkam fi Naqt al-Masahif; Ibn Asakir, Tarikh Madinat Dimashq; Zurqani, Manahil al-‘Irfan fi ‘Ulum al-Quran; Muhammad Bakr Isma‘il, Dirasat fi ‘Ulum al-Quran; Sa‘id Hawwa, al-Asas fi al-Sunna]

This practice closely resembles the current method of coloring certain words in the Quran to indicate specific tajwid rules, which aids in proper recitation.

Preserving the Quran

Scholars unanimously agree on the necessity of preserving the Quran and treating it with utmost reverence, and they forbid exposing it to disrespect or trivialization. The manifestations of honoring the Word of Allah are numerous. Among these are practices reported from the Companions and their followers, as well as the practices adopted by scholars and Muslims thereafter, such as keeping the Quran in a leather or cloth cover, elevating it off the ground, and other forms of respect.

For this reason, Muslims have eagerly competed to serve the Book of their Lord in many ways. Among the services the Quran has received are writing it in the most beautiful scripts, marking its letters, and adding diacritical marks to prevent potential errors in reading.

Additionally, they have marked places of pause and start to facilitate the reader’s understanding of the meaning and prevent incorrect pauses or starts that might distort the meaning of Allah’s words. Scholars have also created symbols to indicate permissible and impermissible pauses within the Quranic text, such as the symbol (ج) for permissible pauses and (م) for mandatory pauses. These symbols are now printed with the Quran and listed at the end under the title “diacritical marks.”

Visual Services for the Quran

In our current time, the visual services for the Quran have increased, and people have become more creative. Some have focused on printing it in the best formats, on the finest paper, with the most beautiful decorations and designs. Special printing presses have even been established to print and distribute the Quran for free, as seen in the printing presses in the holy lands of Saudi Arabia.

The permissibility of coloring certain words in the Quran to indicate tajwid rules also extends to what some presses do today. For example, they color similar verses to assist memorizers in perfecting and distinguishing them, thus preventing confusion and mistakes.

Additionally, coloring verses that discuss specific topics and using colors to indicate these topics is also permissible. For instance, blue might denote signs of Allah’s power in the universe and human beings, His great creation, and His grace and beneficence toward His servants. Yellow might signify the stories of the prophets, their lives, miracles, and the tales of previous nations. Red might indicate Hell and its descriptions and the punishment of the disbelievers. Moreover, some memorizers use colored sticky notes in the Quran to mark similar verses, which might be necessary for them.

Maintaining the Sanctity and Respect of the Quran

However, using fluorescent highlighters or similar markers to shade verses for memorization or review purposes is better avoided to maintain the sanctity and respect of the Quran. The Quran holds great reverence in the hearts of Muslims, and it is essential to preserve this reverence and not diminish it. Excessive shading and marking can lead to the Quran looking like a school textbook or a cultural book, reducing its awe and respect in people’s hearts. The intended benefit of such shading can be achieved through other means that do not compromise the Quran’s sanctity.

Innovations in Serving the Quran

It is worth noting, as we discuss the noble services that the Quran has received, that the diacritical marks, vowel markings, symbols for pausing and starting, and the division of the Quran into quarters, parts, and sections were not present during the time of the Prophet (Allah bless him and give him peace) nor during the time of his Companions (Allah be pleased with them). These practices were introduced later and were accepted by scholars because they serve the recitation, reflection, and understanding of the Word of Allah.

It is also important to note that the early scholars initially viewed the marking and vowelization of the Quran with disfavor, as they were keen to preserve the Quran’s original script and feared that adding these marks might lead to alterations. For instance, it is reported that Ibn Mas‘ud said:

“Keep the Quran pure and do not mix it with anything else.” [Ibn Salam, Fada’il al-Quran]

When Ibn Sirin was asked about marking the Quran with grammatical symbols, he said: “I fear that it may lead to additions to the letters.” [Ibn Abi Dawud, al-Masahif]

Ibn Abi Dawud al-Sijistani reported in his book “al-Masahif” that “they disliked marking, decimalizing, and numbering the suras.” [Ibid.]

Modern Practices and Scholarly Views

However, as times and people changed, Muslims found it necessary to add diacritical marks and vowel signs to the Quran for the same reason the early scholars refrained from it — to prevent the alteration of Allah’s words and to preserve the correct recitation as it was revealed. This necessity led to the ruling changing from the dislike of these practices to their recommendation or even obligation.

The ruling follows the reason for its existence: if the reason ceases, the ruling changes. The dislike of marking was not due to the marks themselves, but due to the fear of adding to or altering the Quran. The same reasoning can be applied to coloring certain words and verses in the Quran. [Nabhani, al-Madkhal ila ‘Ulum al-Quran al-Karim]

Imam Nawawi stated that it is recommended to add diacritical marks and vowel signs to the Quran because it protects against errors in recitation. The dislike expressed by Sha‘bi and Nakha‘i was due to the fear of alteration at that time, but that fear no longer exists today. Hence, this practice should not be prohibited simply because it is new. It is one of the good innovations, similar to the compilation of knowledge, the building of schools, and other beneficial acts. [Nawawi, al-Tibyan fi Adab Hamalat al-Quran, al-Majmu‘; Zurqani, Manahil al-‘Irfan; al-Asas fi al-Sunna]

There has been a disagreement among scholars regarding the permissibility of decorating the mushafs with gold or silver. Some have permitted it, some have disliked it, and some have prohibited it, citing what was narrated from Ubayy Ibn Ka‘b, who said:

“When you decorate your mushafs and adorn your mosques, then expect destruction.” [Ibn Abi Dawud, al-Masahif]

Ibn Athir said: “The original meaning of ‘duthur’ is the obliteration that occurs when the wind blows on a dwelling, covering its features with sand and dirt… and the obliteration of the soul: its quick forgetting. The intended meaning may be that if you do this, the remembrance of Allah will be obliterated from your hearts, you will forget Allah and abandon His mosques.” [Ibn Athir, al-Nihaya fi Gharib al-Hadith]

Indeed, the noble services provided to the Quran will never cease, and coloring the letters to indicate tajwid rules is not the last of these services. As time progresses, Muslims will continue to innovate ways to honor the Book of Allah and make it easier to recite, perfect, and understand, especially in this era of rapid technological advancement.

Conclusion

Finally, anything that detracts from the sanctity and respect of the Quran is forbidden, regardless of the action or its purpose.

It was narrated from Abdullah Ibn Mas‘ud that he was brought a decorated and gilded mushaf, and he said: “The best decoration for the mushaf is its recitation in truth.” [Tabarani, al-Mu‘jam al-Kabir]

O Allah, help us to recite Your Book properly and uphold its letters and boundaries… Amin.

May Allah bless the Prophet Muhammad and give him peace, and his Family and Companions.

And Allah knows best.

[Shaykh] Anas al-Musa

Shaykh Anas al-Musa, born in Hama, Syria, in 1974, is an erudite scholar of notable repute. He graduated from the Engineering Institute in Damascus, where he specialized in General Construction, and Al-Azhar University, Faculty of Usul al-Din, where he specialized in Hadith.

He studied under prominent scholars in Damascus, including Shaykh Abdul Rahman al-Shaghouri and Shaykh Adib al-Kallas, among others. Shaykh Anas has memorized the Quran and is proficient in the ten Mutawatir recitations, having studied under Shaykh Bakri al-Tarabishi and Shaykh Mowfaq ‘Ayun. He also graduated from the Iraqi Hadith School.

He has taught numerous Islamic subjects at Shari‘a institutes in Syria and Turkey. Shaykh Anas has served as an Imam and preacher for over 15 years and is a teacher of the Quran in its various readings and narrations.

Currently, he works as a teacher at SeekersGuidance and is responsible for academic guidance there. He has completed his Master’s degree in Hadith and is now pursuing his Ph.D. in the same field. Shaykh Anas al-Musa is married and resides in Istanbul.